LONDON: An imposing gateway that appears to lead nowhere, situated somewhat incongruously on a triangular island created by the intersection of three major roads in the west of Riyadh, is nowadays something of an architectural mystery, even to many of the city’s inhabitants.

Yet the Nasiriyah Gate bears mute testimony to the rapid growth of the capital, from a small provincial town in the 1950s with a population of little more than 125,000 to a globally significant city that is now home to over 7 million.

The remarkable story of the Nasiriyah Gate, and the now forgotten spectacular palace complex to which it was once the eastern entrance, emerges in one of a series of rare documents and books to be offered for sale at the Abu Dhabi International Book Fair at the end of May.

With little surviving information about the short-lived Nasiriyah Palace, historians will find a wealth of detail in what is thought to be one of the few surviving original plans for the vast palace complex, which was once surrounded by a pink-hued wall over 11 kilometers in length.

The grounds of the extravagant site included homes for members of his immediate family, a garden and fountains. (Social Media)

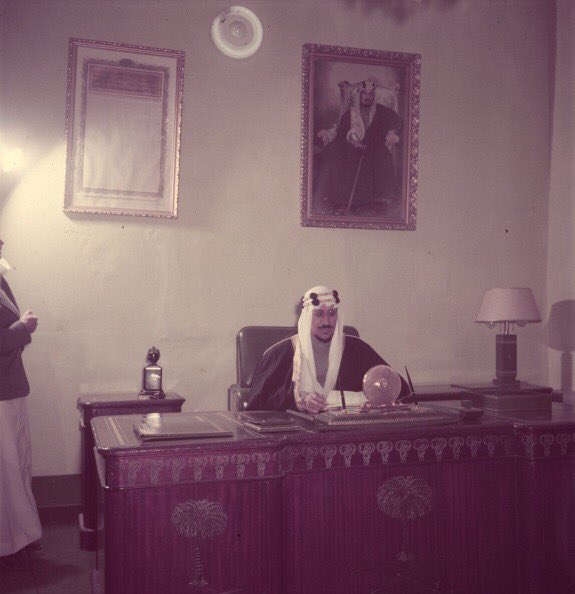

The palace was commissioned by King Saud bin Abdulaziz Al-Saud after his accession to the throne in 1953. The masterplan for the complex, which is being offered for sale for £17,500 ($21,544), is thought to date from about 1954.

“It is a remarkable and significant document, one of the few surviving original plans for the extraordinarily opulent royal palace built for the king by his ‘royal builder,’ Mohamed bin Laden,” said Glenn Mitchell, antiquarian bookseller at Peter Harrington, the London rare books dealer offering the document for sale.

Incidentally, as crown prince Saud had already built a palace on the site, which at the time was barren land to the west of the city. According to one account, within its gates “an avenue of tamarisk trees ran through a garden of flowers, lawns, and caged birds and a blue-tiled pool fed from wells tens of thousands of feet below the ground.”

It was, said Mitchell, “an almost make-believe environment that seemed to be a blending of the modern with something conjured from the Alf Laylah wa-Laylah, the One Thousand and One Nights.”

The palace was commissioned by King Saud bin Abdulaziz Al-Saud after his accession to the throne in 1953. (Social Media)

Upon Saud’s accession in 1953, the first Nasiriyah Palace was deemed to be too modest a residence for the ruler of a Kingdom rapidly growing in stature on the world stage. It was replaced with the new complex.

The new complex, in turn, would be demolished within 10 years, sacrificed to the rapid expansion of Riyadh.

Of the Nasiriyah Palace demolished in 1967, according to Mitchell, only one of the main gates and some fountains survive today.

“There is very little information surviving on the complex,” he said. “This plan reveals a tremendous amount about the palace and the life of the royals. It shows a vast site containing numerous royal residences, and an array of supporting and recreational functions.”

The plan reveals the astonishing extent of the complex — a township in its own right — featuring the King’s palace and other palaces for members of the royal family.

Blueprints of royal residences are among the documents that will go on sale at the Abu Dhabi International Book Fair (May 23 to 29). (Supplied)

There were entire districts of villas for princes and princesses, schools for boys and girls, extensive gardens, a hospital, mosques, library, museum, a power station, water reservoir, electricity generating plant and accommodation for staff including servants, janitors, teachers, storekeepers, royal guards, laborers, engineers, nurses, caterers and a “keeper of the Qur’an.”

Today, another echo of the lost palace can be found in the name of the highway that passes by the forlorn gateway — the King Saud Road — which begins here and runs east for 2.5 kilometers through the modern city, past the Ministry of Foreign Affairs toward Murabba Palace, the former home and court of Saud’s father, King Abdul Aziz, the founder of modern Saudi Arabia.

King Abdul Aziz lived at Murabba Palace from its completion in 1938 until his death in 1953. Built in the traditional Najdean architectural style, on farmland outside the walls of the old city of Riyadh, the relatively modest building, a significant waypoint on the nation’s journey, has been perfectly preserved.

By a curious coincidence, documents related to another piece of Riyadh’s architectural history, situated within a couple of hundred meters of Nasiriyah Gate, are also on their way from Britain to be displayed and sold at the Abu Dhabi book fair.

For generations, the main entry point to what in 1932 would become Saudi Arabia was the port of Jeddah, and it was here that foreign diplomats and embassies were based for decades.

Nasiriyah Palace of King Saud. (Twitter)

By the early 1970s, however, the advent of commercial air travel had rendered seafaring all but redundant. And so, in short order, Saudi Arabia’s foreign ministry and the diplomatic missions of other countries were packed up and moved to Riyadh.

In 1975, land was acquired for the construction of a diplomatic quarter and the new headquarters for the foreign ministry. This area of 10 square kilometers was just a few hundred meters from the former Nasiriyah Palace complex.

Work began in 1980 on what the master plan for Riyadh described as “a proper setting for international diplomacy” — a 120-plot model for Riyadh’s urban development, and a boost to intercultural understanding.

The grand project took five years to complete, with individual countries commissioning buildings for their embassies from leading architects.

Nasiriyah Gate bears mute testimony to the rapid growth of Riyadh, from a small provincial town in the 1950s to the gloabl metropolis of today. (Social Media)

Once completed, alongside the featured diplomatic missions, each vying to outdo the next in architectural excellence, the quarter featured residences, mosques, schools, shops, and other recreational facilities.

The quarter also boasted 377 kilometers of water pipes, 490 kilometers of electrical and telecoms cables, 50 kilometers of roads, extensive gardens abundant with local plants, and — far ahead of its time — a computer-controlled irrigation system run on recycled sewage water.

In 1989, one Aga Khan Award for Architecture went to the stunning Ministry of Foreign Affairs building at the heart of the quarter, and another to the entire diplomatic quarter, for its “realistic and imaginative understanding” of Riyadh’s desert environment.

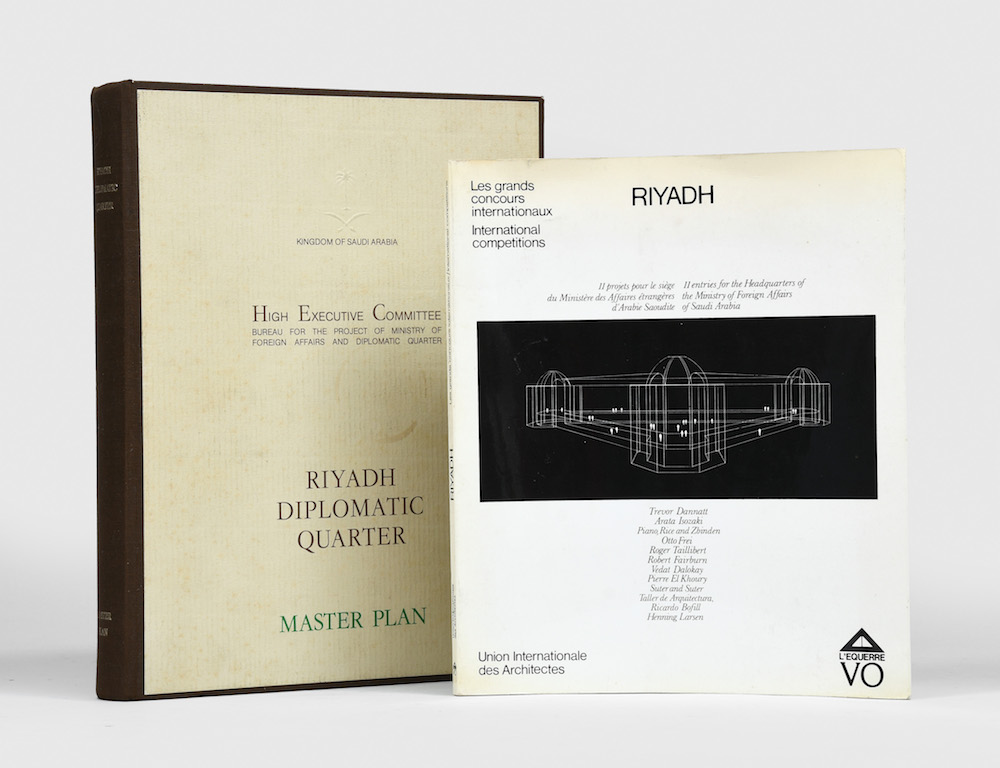

For students of architecture, and historians interested in the evolution of Riyadh, the rare copy of the master plan for the diplomatic quarter, prepared by the German design consortium and now offered for sale for £2,250 ($2,767), is a treasure trove of information.

A rare collection of architectural plans charts the Saudi capital’s evolution from small village to global metropolis. (Social Media)

The document, said Duncan McCoshan of Peter Harrington, “was intended to present Riyadh’s governor, Prince Salman Ibn Abdul Aziz, with a summary of background information, including existing arrangements in Jeddah, the development program, physical planning, and an implementation plan, drawing on a host of sector papers, studies, plans, and reports.”

Only three other copies of the master plan are known to exist, held at the University of Houston, Universitatsbibliothek Kaiserslautern, and Deutsches Architekturmuseum.

Included with the master plan is a rare copy of the booklet “Riyadh: 11 entries for the Headquarters of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Saudi Arabia,” a fascinating document that describes the international architectural competition that in 1980 led to the selection of Danish architect Henning Larsen’s award-winning design.

The 31st edition of the Abu Dhabi book fair will run from May 23 to 29 at the Abu Dhabi International Exhibition Center.